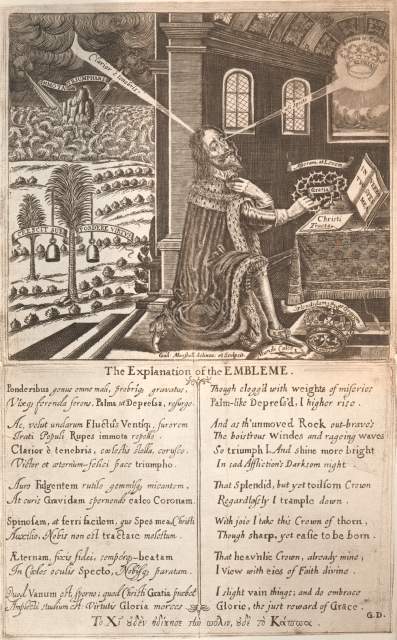

The image of the Eikon Basilike was engraved by William Marshall (fl. 1617–49) and produced within days of the King’s martyrdom.

The image of the Eikon Basilikewas engraved by William Marshall (fl. 1617–49) and produced within days of the King’s martyrdom. It was of such popularity that Marshall had to re-engrave the plates eight times.

The design of the image has many similarities with Titian’s painting S.Catherine of Alexandria (c1568). Marshall would have known this painting for it was in King Charles’s very own collection of paintings.

The eminent engraver Wenceslas Hollar (1607–77) also produced a version of the Eikon Basilike in 1649. This version depicted the King as the Princely Pelican offering his martyr’s blood for the good of the Church. It was still popular even in the eighteenth-century when Robert White (1645–1704) engraved a folio-sized version at the turn of the century and John Smith (1652–1742) produced a fine mezzotint in about 1710.

The Eikon Basilike shows S.Charles kneeling in a chapel, with the same facial expression Christ had during the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane. He looks up with the same agonised expression as Christ was conventionally depicted when asking for the cup of suffering to be taken away.

S.Charles kneels against a vested altar, grasping a crown of thorns placed equidistantly from his earthly crown, which is discarded at his feet and lies inscribed with the word Vanitas (vanity). Before him is a vision of a heavenly crown inscribed Gloria (glory). The iconography is clear. It is only by grasping the crown of thorns that the martyr can aspire to the true crown.

The whole image spells out the parallel between this earthly king and the King of Heaven; redemption came for both through suffering. The background includes an emblematic landscape of the kind favoured in illustrations of the period: the rock of constancy in a stormy sea, being struck by lightning bearing the inscription Immota Triumphans (unshaken and triumphant), and the palm tree with pendent weights and a scroll inscribed Cruscit Sub Pondere Virtus (virtue grows under burdens).

The engraving, as here, was often accompanied with verses explaining the different details, although for many contemporaries these words would have been redundant for the iconography was strikingly comprehensible.