On the morning of 30th January, 1649 Charles awoke early and told his attendant Thomas Herbert, “this is my second marriage day… for before night I hope to be espoused to my blessed Jesus.” The winter weather was so severe that the Thames had frozen over. The King was concerned that the cold would make him shiver giving the appearance of shaking with fear, so he asked as he was dressed to be provided with an extra shirt for warmth (one of these shirts is kept at Windsor Castle and the other at the Museum of London).

William Juxon, Bishop of London, arrived to read Morning Prayer with the King and to administer the Sacrament. The Bishop read the lesson for the day, which was the account of the Passion of Christ. Charles thought that this passage had been especially chosen by the Bishop but was told that it was the proscribed lesson in the Prayer Book for that day. The King found this very reassuring.

At ten o’clock Colonel Hacker told the King that it was time to leave for Whitehall. Charles, Juxon and Herbert were escorted on foot from S.James’s Palace. Two companies of infantry guarded the route. The party was led through the inside of several buildings to avoid the gathering crowds. They passed over the upper floor of the Holbein Gate from where Charles would have seen the scaffold below and then into the Banqueting House.

It was intended that the beheading should proceed immediately but the official executioner, Brandon, refused the task in horror. There followed a search to find someone to take his place. The identity of the man who finally wielded the axe remains a mystery, for he and his accomplice wore masks. About three hours had elapsed with cruelly Charles being kept waiting. It is sometimes suggested that the delay was caused by a last-minute sitting of Parliament to pass an Act prohibiting the proclamation of the Prince of Wales as King. However, this had been done the previous Saturday, and anyway, many members of the House had deemed it expedient to be absent from the City that day.

The wait must have been extremely trying for the King but all those around him remarked on his calmness and composure. Midday arrived and a meal was prepared for him, this he refused having resolved to take no food that day other than the Blessed Sacrament. Fearing that the lack of food and passing of time would cause the King to feel faint, Juxon persuaded Charles to eat just a little. He was presented with a small loaf of bread and a glass of claret; thus he had his Last Supper. He spent much time in prayer with the Bishop.

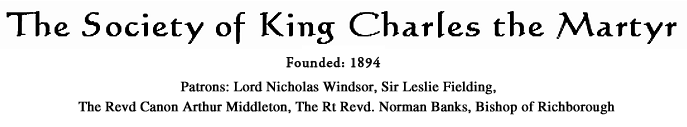

Sometime after one o’clock all was ready on the scaffold. The King emerged from the relative gloom of the Banqueting House, where many of the windows had been boarded up, to the brightness outside, where the sun had broken through the clouds. The street was packed. Ranks of soldiers, on foot and mounted, filled the area near the scaffold preventing any rescue attempt. The public were kept at a distance so that they could see and hear very little. The railings of the scaffold were hung with black drapery to obscure the view further. In the centre of the platform was a low billet of wood with attached ropes and staples in case the King resisted and needed to be secured to the block. A cheap deal coffin, which cost ‘but six shillings’ lay to one side with a black pall to cover it.

With Charles were Juxon, Colonel Tomlinson, Colonel Hacker, the two headsmen and two or three shorthand writers. To the witnesses Charles appeared to be fully confident. He had been denied the right to speak freely at his trial after the sentence was passed and although he realised that few would hear him he spoke to the crowds. He declared himself to be “an honest man, a good king and a good Christian” and that he had not begun the Civil War and that he considered his sentence illegal. He added though that he was receiving just punishment from God, a reference to his allowing the execution of Strafford earlier in his reign to placate the puritans, which he bitterly regretted and repented of.

He said that his desire was for liberty, freedom and the rule of law and government and not for arbitrary rule; for all this, “I am a martyr of the people.” He concluded by saying, “I die a Christian according to the profession of the Church of England as I found it left to me by my father…I have a good cause and I have a gracious God.”

He then spoke words of forgiveness to the two headsmen and explained that he would give a signal when he was ready for the axe’s blow. Juxon helped the King to tuck his long hair into a cap so that it might not impede the axe.

The Bishop said, “There is but one stage more which though turbulent and troublesome, yet is a very short one; you may consider that it will carry you a very great way; it will carry you from Earth to Heaven, and there you shall find to your great joy, the prize you hasten to; a Crown of Glory.”

Charles replied, “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown, where no disturbance can be, no disturbance in the world.” He then passed his George to Juxon and said, “Remember!”

Charles stood for a moment in silent prayer, then lay down with his head on the block. After a few seconds of prayer he stretched out his hands as the sign. The ‘bright axe’ flashed and at one blow Charles’s head was severed from his body. Contemporary accounts record that a great groan went up from the crowd. One of the headsmen held up the blessed martyr’s head and against custom, did so in silence. Sir William Sanderson, who was a witness, recorded that the fatal blow was struck within a minute to two o’clock.